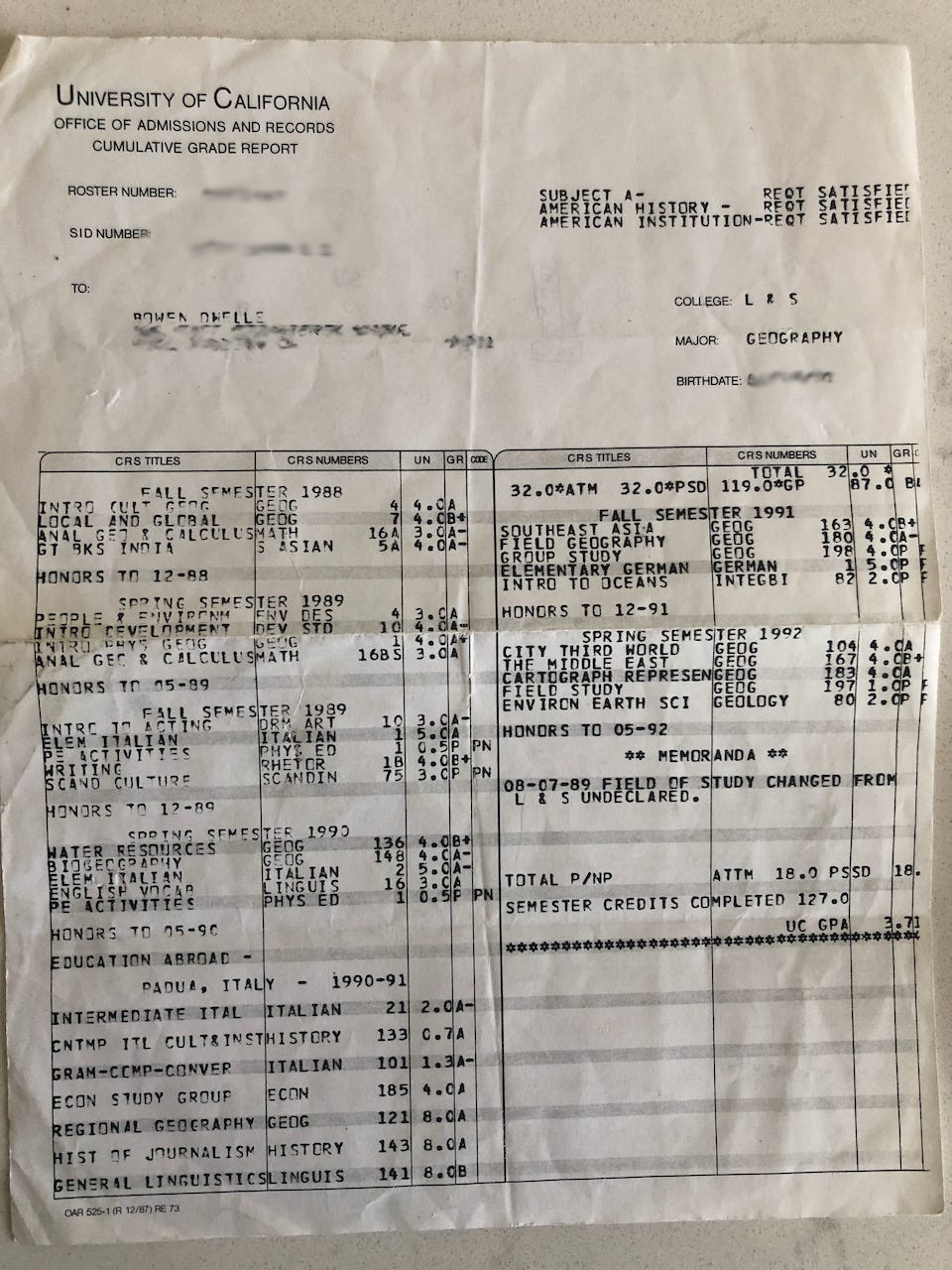

The phrase “Things Fall Apart” has been stuck in my head since I read Chinua Achebe’s novel in my first year at Cal Berkeley. Looking back at my 1990 transcript, I took Development Studies, Scandinavian Culture, South Asian Literature, Acting, Linguistics, and even something called “Writing,” along with many courses from my major in geography. I was interested in words, languages, and the use of language—and also in place, nature, the shape of the world and how we inhabit it. I only scored a B+ in writing. Geography was more concrete, less abstract, and more real. It offered a way to make sense of the world that I could see all around me. It shows how everything is connected, from the slope of a hillside to the neighborhood built upon it, to the lives of the people who live there.

Geography is not an anxious science. I loved it, and I still do. Perhaps if it had occurred to me to continue down that road, I’d be a less anxious person today, a contented and loquacious professor of geography, office hours posted on the dark oaken door of my serene university office.

Things fall apart accreted like a grain of sand into my own cellular canon along with “The center cannot hold,” which, I’m sure, I came across in reading Joan Didion, who used that latter phrase so often that I assumed it was hers, even as I could simultaneously hear quite clearly that she’d borrowed it from someone else. My reading ear added the italics of attribution.

“The center was not holding” in everything from Slouching Towards Bethlehem to David Carr’s The Night of the Gun, I imagined that he wanted me to be sure that he’d read Didion too. I don’t know if he thought it was her that he was borrowing from, but seeing the reference again prompted me to look it up, and now I know that the source of both phrases is Yeats, and that they originate in a single line of his poem The Second Coming. They’re two versions of the same sentiment, conjoined from the start, a restatement for emphasis:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

Not that knowing makes it any easier, but we all know how things fall apart—they have, they do, they are, and they will. I’d have to read Achebe again to re-learn what sense he made of the treble undoing of colonialism, indigenous Nigeria, and his own self, but for me, the threat of not just things falling apart, but of everything falling apart—of an unqualified falling apart—that is the existential fear that plagues me. With even the slightest touch, the rotten claw of falling apart reminds me of its hold on me. It’s unlikely that my own falling apart has anything specific to do with Achebe’s, but, clearly, a disintegration in the center feels familiar to enough of us, regardless of cause or circumstance, that both phrases get frequent play.

This constant sense of falling apart could be a mirror image of the forever-forward striving of human aliveness, a slow, entropic undoing that is just as wired into us as the perpetual dissatisfaction that, paradoxically, drives us forwards. A braking force, then, that unwinds the spring and weighs on the escapement, those grains of sand sifted down into the gears now, jamming up the works, slowly, from the inside.

Things fall apart. Things wear out. We’re all wearing out—but here’s the thing—as I’ve gotten healthier and, in relative terms, more stable over the past decade or so, the big things that used to bother me in the sense of actually causing some material undoing have been replaced by smaller things that cause less bother in real terms, but moreso to the psyche.

What I’m saying is that for example, it should have bothered me that I used to pour myself two or three tequila cocktails every evening, regardless of where or whether I was with anyone else or not (usually the latter), to be followed by at least half or most or all of a bottle of wine. This often felt enjoyable, but also caused me actual pain and damage—and even so, it generally didn’t trouble me much at the time.

It should have bothered me that my back still gave me hurt on a regular basis after injuring myself years before, and that I knew what I had to do to keep the pain from recurring, and that I didn’t do it—but instead, for the most part, I took a pill now and then and did my best to ignore the truth, hoping that eventually “it” would go away. The truth never goes away.

It should have bothered me when I was, let’s say, dating someone that I felt half-hearted about but didn’t have (no wonder) the heart to let go of, because of what was my own not really so unique style of “attachment” in relationships—that is, most of all, desperate. All of those things should have bothered me, but they didn’t, at least not enough for me to take much notice at the time.

I’ve since swept those more obvious skeletons from the closet, and I live so damn clean these days that you might well find it boring at times. By rights, I shouldn’t be bothered at all, but the thing is, now I am bothered—by the little things.

I’m bothered by the corners of the bathroom floor where the grout was applied without proper tools and left rough and wrong. Run a sponge down the seam and instead of clean you’re left instead with shreds of abraded sponge stuck to the sticky-outy bits of a half-assed tile job. I glance down while taking a piss and I swear I can feel all of these little blobs swimming like plaque in my cerebral blood vessels, tiny bits of flotsam that threaten sudden catastrophe.

I’m bothered by how little stains and particles of food collect on the too-small and poorly sealed square of wooden butcher-block counter-top in my otherwise fairly shipshape little kitchen. Each one feels like a crack in the china of my well-being. They weaken me.

I’m bothered by how one of my jackets always slips off the coat rack unless carefully backed up with another, heavier garment. Whenever the lighter one does slip off, as it does about half the time I go to hang it up, I stifle or let out an exasperated shout—the same “fuck!” that I’d yell if I backed the car into a tree—and although I did do exactly that the other day, dropping a down jacket on the entryway floor is nothing nearly so much to get upset about. And yet, I often give a involuntary yelp of frustration—and fear.

The fear of things falling apart.

These tiny things, they feel unreasonably likely to grow into much larger undoings—into the undoing of everything. Just a drop in the bucket, but then the bucket gets kicked over, the water never stops, the floor is flooded, the drywall is ruined, the mold grows unnoticed…it makes no sense, but it feels like the center of my self could come apart. The ship is sinking.

I feel my mother in this anxiety—her unsteadiness, her jumpiness, her sudden shouts of surprise, her avoidance of the truth. A word of hers—flustered—that sounds like an distressed chicken having wandered away from its pen. Flustered: a word that has no business in me, not individually, and certainly not in a “man” (in quotes of course). Fearful. Anxious. Fragile. Unstable.

Another unsuitable word—chicken.

What am I afraid of?

I’m afraid of my own undoing.

Undoing confidence. Undoing calm. Undoing coherence. Undoing steadiness, ability—and sanity.

Why would I be so afraid of not being able to keep my shit together? I’ve never been that guy. I do my taxes. I change the oil. I keep things clean… but it’s closer than it seems.

That’s the heart of it right there. It doesn’t really matter how much effort is required to keep the whole operation going. I know I’ve got it comparatively easy. It’s not quantitative though—it’s the quality of feeling that unhinged is just…closer than it should be.

Writers especially of course, many of them are dangerously close to the edge. Perhaps some of you—those that don’t write?—don’t feel the risk at all. Some folks feel anxious most of the time, some only once in a while. Others oscillate between periods of breakdown and euphoria, ‘rock bottom’ and heights of brilliance. I’m not quite so much a person of extremes, so I feel the risk of the wheels coming off in more subtle ways, let’s say 20-30% of the time.

I’ve written elsewhere about discerning the difference between intuition and fear, or, really, anxiety. Anxiety has to do with an imaginary future that feels unpleasant—in the present. It’s a persistent fantasy that’s icky enough to give us goosebumps. It’s not that I actually have nothing to worry about, but, in real terms, I have very little to worry about. I know that anxiety is false.

Everything seems even more than fine much of the time, but it’s doesn’t take much to upset the balance, which is far more delicate than I would like. Even so, the evidence of my life—observing the animal in the wild, so to speak—shows that even with a few real regrets along the way, I have managed to do just fine over time, so again, why the so-frequent fear that it will all come unspooled?

I’ve come to feel that there really isn’t any other explanation other than that this present anxiety is an echo of past anxiety. A habit of anxiety. A pattern that recurs in the present not because of some proximate cause, but because the path exists from prior journeys. Tracks of anxiety laid down—when else—in the small-“t” trauma of my youth, in loneliness, in losing myself, in fear that was real—then.

But not now.

I wrote recently about the voice of “I don’t want to,” and “I can’t,” how those voices still come up within me, and how I’ve been confronting certain versions of them lately. Looking them in the eye with the knowledge that whatever truth they held in the past is no longer valid. That “I can,” and that the voice of my present real self is more important than the echo of the past, however deep its rumbling.

Perhaps I can do the same with this anxiety. I know this is why some people do go even more to extremes—to more forcefully confront that voice of “I can’t.” I’ve done my share, but Resistance doesn’t give up—it keeps coming back and trying different tactics. As much as I wish that at some point I’ll come be able to declare some sort of permanent victory, that doesn’t seem to be possible. I have to keep discovering new ways to dig through the shadow, as it continues to be unearthed.

That’s true about the “shadow,” and it also sounds a bit vague. There’s always more to be revealed—and, the fact is, I know exactly what I need to do, at the moment. I’d like to, but I don’t need to run marathons. I’d like to, but I don’t need to fly paragliders again, not right now. I’d like to cross the oceans, I don’t need to go there, not right this second. I don’t need to escape.

What I need to do is 1) work out every morning—as I have since sometime in December, 2) to be mindful of and reduce my screen time, especially first thing in the morning and in the evening. My morning routine (I have one, for the first time in my life!) is hot drink, quick walk outside, read a little, exercise, breakfast, and then work. I don’t want to look at a screen at least until breakfast. I feel kind of gross if I do, just as I do if I watch too much YT before bed; and 3) learn to meditate. I mean, I know how to meditate, but I still haven’t made it a habit, despite how I know that it could well be true that “prioritizing the inward practice always has the highest payoff of any activity.” I can feel the difference in my mood and creativity even after just four days of daily meditation, and I know intuitively as well as objectively that it would make a big difference for me to keep this up—and so I will.

In a way that feels new to me, I am actively confronting the chant of “I can’t,” “I don’t want to,” “I’m stuck” and “I don’t know what to do” and converting those to “I can,” “I am doing exactly what I want to be doing,” and “I am happy to be right here, right now.” I see this guy Mike Posner practicing ‘wiring that shit in,’ which reminds me a lot of David Goggins’ “Stay Hard” messages—similar but different. I love both of these guys, and I have something to learn from them, too.

The one, two and three that I just cited don’t include things that I’m already in the habit of doing, including: not drinking alcohol at all, using “Let Monday Be Truth Day” to avoid letting emotional overhead build up, sleeping well, being active outside as much as possible, and… a whole string of other things. I’ve also been shifting towards eating more protein and eating less in the evenings, although as a San Francisco native, I still love me an It’s It or a cone from Swensen’s or Gio Gelati for dessert.

There’s one more big thread running through this anxiety. As Kathryn Bond Stockton puts it in Gender(s), “Ideals are brutal. You can’t help but fail them, since they are ideal. That is, not real. If the ideal you fail, moreover, is the ideal that ‘you must not fail’—this is masculinity—you are going to be a failure…” Now, I don’t feel like a failure, nor do I think of myself as a failure, and I don’t consciously worry about failing ‘as a man,’—but the fact is that, for most men, fear of failure is as deeply wired in as anything else in our makeup. Just as much as masculinity demands success, it also requires failure.

I know it’s not fashionable now to be seen as crying wolf about anything as a man—and the fact is, it never was. There’s the double bind—not speaking up against anything about masculinity is part of how masculinity is defined, and yet now, speaking up about masculinity at all is at risk of gathering shade for taking the spotlight away from everything other than the masculine.

That’s all fine though, really. I’m not asking that you cut me a break—I’ve had my share.

All of us, not just men, learn that we must not fail. We must not break down, collapse, let the screws loosen too far. We have to keep it together—and yet, just as gender is falling apart, masculinity is also one of the things that is falling apart.

Lots of us have been asking—and rightfully so—what is masculinity becoming? What should it become? What do we need it to become?

The best answer that I can see at the moment is that it’s not so much a question of what will masculinity become, but when will it come to an end? I’m not advocating for that, and nor am I saying that it’s inevitable, but it does seem possible, and I’m not necessarily against it. If what it has been to be masculine was to aspire to an ideal that was always impossible to achieve, then the best way forward is to deconstruct, to seek to fail the tests—to go beyond passive resistance to actively taking things apart—and those things are ourselves. The “system of rewards” that have nominally accrued to men itself depends on our complicity in the system that grants those rewards—and it’s painfully obvious that that system is working for nobody.

That’s part of what’s showing up in my nervous system—the deeply-wired anxiety of trying to pass an impassable, impossible test. Of having to continually show that I’m invulnerable to everything—and so, perhaps no wonder that it’s the smallest, seemingly most subtle reminders of my vulnerability that leave me feeling so girlishly flustered.

It occurs to me that I must fail these tests to create space for something new. I must fail at not being anxious, so that this anxious can come apart. In the coming days, I will be asking myself: how can I fail?

—

Previously Published on substack

iStock image

internal image courtesy of author

The post Anxious Masculinity—How Things Fall Apart appeared first on The Good Men Project.